Marketing Discovery: Whither PhDs?

Peter Drucker said marketing makes selling superfluous. Today? We are effectively cold-calling geniuses to accept near-minimum wages for a 20% shot at a job. The legacy PhD model is broken. It’s time to stop selling an academic lottery ticket and start engineering a levered asset.

Every year, usually around February, the "Great Sift" begins.

This is the season where the research strategies and delivery plans collide with the hard reality of PhD recruitment. We sit in offices or meeting rooms reviewing the CV's of the brightest candidates from across the globe (41% of UK doctoral students are international). For decades, the ritual of matching project, supervisor and student was an extreme example of negotiation asymmetry and winner's curse: academics held the keys to knowledge and resources, and the PhD was the only ticket to the game.

But the dynamic has shifted. Candidates are still brilliant, but instead of trying to impress us, they are now auditing us. They weigh the UK stipend and potential for contribution to knowledge against international opportunities, R&D roles in Series B start-ups, or quant positions in the City. Suddenly, academics find ourselves having to sell.

Peter Drucker famously noted "The aim of marketing is to make selling superfluous". For a long time, the PhD product was so unique it sold itself; we didn't need to market discovery. But today, home students are increasingly unconvinced by the value proposition. Through the dispassionate lens of an MBA, we must consider stopping seeing students and supervisors, and ask: are we trying to sell a legacy product in a market that has been disrupted?

A Distorted Market

If we strip away the history, cultural context and romance of a PhD and treat the PhD as a standard product offer, the spec sheet is concerning.

The cost to the student is threefold: tuition (£4.8k/yr for home, up to £40k/yr for overseas), time, and opportunity. A 4-year PhD represents a significant chunk of prime earning potential. Even with a tax-free stipend of up to £31k/yr, the opportunity cost compared to a graduate role in tech or finance is stark - conservatively £100k over the period.

Historically, the value proposition (VP) was the mix of unique training, a powerful network, and critically a qualification that acted as "moat" to guarantee long-term ROI. However, in recent years wage inflation has eroded the value of the stipend and postgraduate qualifications only provide a 15% lifetime pay increase over an undergraduate degree. Furthermore, the democratization of knowledge has weakened the "access to knowledge" VP.

Intriguingly, the university brand has never been stronger: Oxford received 8 applications for each of their 620 positions in science and engineering in 2024 - up from 4.8 a decade ago. Yet, despite a 22% increase in undergraduates and 82% increase in Masters students over the past decade, PhD numbers remain flat at ~35k entrants per year.

The customer base is sophisticated. Prominent "drop-out" voices reflect the changing perceived utility value of the degree. While holders remains rare (<2% of the population), there is a risk that it is seen decreasingly as an intellectual pinnacle and increasingly as a career liability - particularly for domestic applicants, who clearly see the high attrition rate to permanent academic research.

The sector must confront uncomfortable questions: we must not only ask what the value of a PhD is, but also to whom - students, industry, society or to the Universities themselves?

Marketing and Delivering the PhD

Marketing is the activity for creating, communicating, delivering and exchanging offerings that have value. Universities have created a PhD product, and now seek a market. In business literature, this product orientation, is synonymous with marketing myopia; build it and they will come, with little consideration of the customer.

Approaching a service product in this was leads to a communication breakdown: despite the assumptions of students, less than 20% will go on to an academic role. The sector relies on an assumption that the best talent will naturally find its way to us; attrition is tacitly viewed as a filter for grit and resilience. This stance is increasingly dangerous. We are witnessing a global bifurcation: while US institutions freeze admissions under funding pressure, Canada has launched a targeted $1.2bn strategy to poach that very talent.

We rely on passive recruitment of survivors, rather than active cultivation of talent, with academic encouragement a key aspect of communicating value. Crucially, this passive "filter" is not neutral; it disproportionately selects against those without financial safety nets or with caring responsibilities, narrowing the diversity of the talent pipeline before it even starts.

If we view the PhD as a service, the SERVQUAL model can be used to understand delivery, measuring the gap between expectation and experience. The typical PhD fails on Assurance (we cannot convey trust that what we provide will deliver what the student wants) and tangibles (the stipend and resources fail to meet student needs). And when our delivery fails, the impact is brutal: a 2024 study showed a 100% increase in mental health medication in Swedish doctoral students.

This under-delivery goes beyond the loss of a loyal advocate. Our current cohort should be the most powerful marketing channel, but dissatisfaction inverts this feedback loop; the message to the next cohort moves from "join us", to "don't do it".

Segmentation is the Story

In marketing, when a single product fails to satisfy a broad market, you segment. The sector should go further to make the implicit variance in PhD offerings explicit: from a PhD by performance, to a professional doctorate, a PhD by enterprise (EntD) or a PhD by innovation.

While we debate the format of a thesis, global competitors are redefining the deliverable. China’s move to award PhDs for deployed utility rather than written theory isn't just an academic quirk; it’s a national industrial strategy. They are building a pipeline of CTOs; we are still building a (leaky) pipeline of Professors.

This pivot to utility exposes a flaw in our pricing. We price the PhD based on the cost of inputs (lab time + stipend). We should be pricing it based on the value of the output (IP generated + career trajectory). Because we use cost-plus, we treat the PhD as a commodity. If we switched to value-based, we would be forced to increase the quality of the training to justify the 'price' (time + effort).

We are beginning to see this shift with the UKRI TechExpert stipend, where specific skills command a premium. However, we must remain alert to the equality impact of this shift: if we prioritize market-rate stipends only for historically male-dominated deep-tech fields, we risk institutionalizing a two-tier, gendered system of research value.

The buyer is not the (only) beneficiary

A unique twist of the PhD is that the value is not only to the student: the supervisor, the institution, the region and the country are stakeholders in the success of the student.

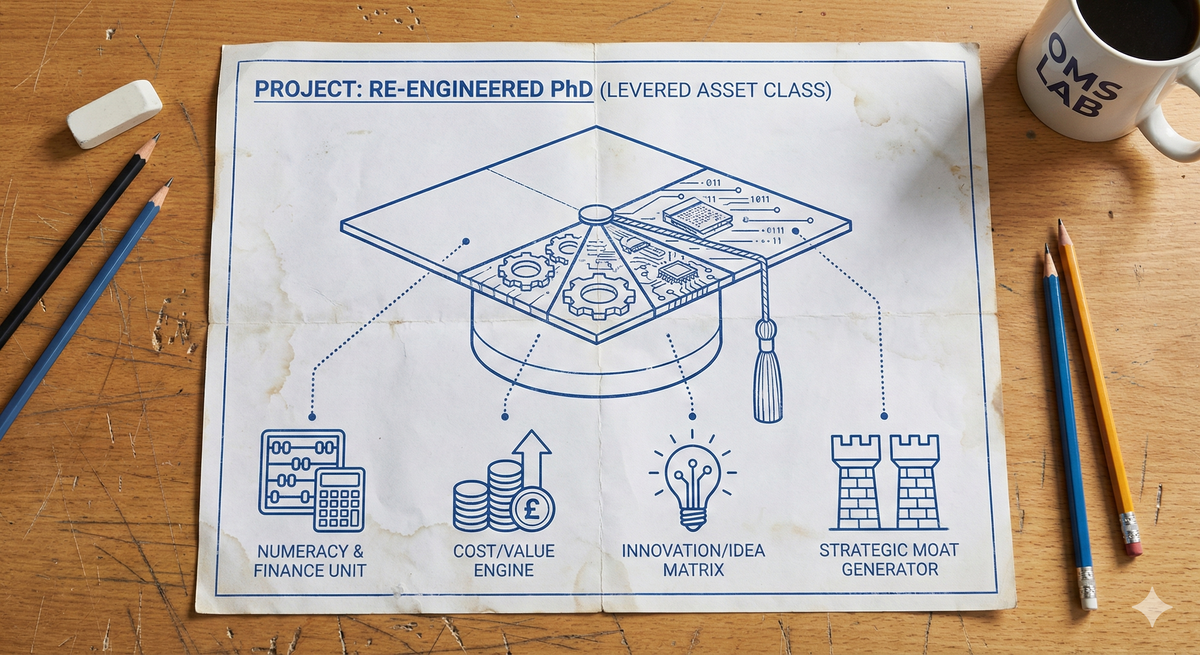

We must therefore change our lens: the generic PhD is akin to an unleveraged asset, appealing to the needs of one stakeholder (e.g. institution = research volume), but failing to deliver value to the student or the economy. Conversely, we can consider a levered PhD that meets the needs of multiple stakeholders: economic growth, research status, IP and reputation and for the student as a defensible career moat.

This is not a call to commoditize education; but to sustain it. Blue-sky thinking across science, humanities and the arts have immense and long-tail societal value. However, we must be honest about who pays for this value: if we ask students to bear the full cost through low wages and high opportunity cost, we create a barrier to entry that creates social exclusivity.

The "General PhD" - unaligned with strategic priorities, student needs, or career pathways - is drifting towards being a consumption good; an experience purchased for personal fulfilment, with limited ROI for stakeholders. In contrast, an envisioned levered PhD is an investable asset. The total addressable value is not just the thesis; it is the sum of utility derived by all stakeholders.

Re-Engineering the Product

To save the PhD from becoming a consumption luxury, it must meet the needs of the modern research ecosystem. This requires a shift from product to customer orientation, and acknowledging the tension: the students hold market power, but suffer information asymmetry regarding long-term value.

We must optimize the sum of value across the stakeholder map:

- For the student (Buyer): The value proposition must shift from "academic lottery ticket" to "Career Moat". This means embedding valuable, rare and inimitable skills into the core curriculum - numeracy, critical thinking, communication, finance, and strategic management in addition to technical domain expertise.

- For the university (Vendor): Different PhD products require different resourcing - and that's fine. If the sum of value is high, the cost of delivery can be justified. It is essential that the leveraged value of every route to PhD is considered holistically.

- For the sector (Regulator): We must recognise that the PhD customer holds the power, but under the current system often lacks the data to see the full value. The sector's role is to bridge this experience gap, to make the case for the sum of value argument. BBSRC's Professional Internships for PhD Students (PIPS) provides a model of mandatory, diverse work experience.

- For Industry (The Consumer): DeepTech doesn't just need Python scripts; it needs technical leaders who understand IP strategy, unit economics, and team dynamics. The 'Levered PhD' de-risks the hiring process for high-growth startups.

We're selling a legacy product in a disrupted market. But, legacy products can be pivoted. The PhD can be unbundled from its academic apprenticeship history, and rebuilt as a high-value asset with explicit multi-stakeholder value.

Whither PhDs? Towards a model where the "Product" is not judged on the narrow output of the thesis, but on the holistic, compounding societal and economic return delivered to the individual, the region, and the economy.